Ageing

Page updated: 25 December 2020

This section explores how the age of the New Zealand population, and commensurate increases in dementia, are likely to impact on Search and Rescue (SAR) demand.

New Zealand's Population is Ageing

Through the 2018 census we can see that the ageing of the population is progressing broadly as projected.

The number of older people rose from 13% to 15% of the total population by 2019.

Looking ahead, one in five New Zealanders will be aged 65+ by 2031 (an increase from 1 in 8 in 2009).[i] Furthermore, the numbers of people aged 85 years and older will more than triple, from about 83,000 in 2016, to between 270,000 and 320,000 in the next 30 years.[ii]

This population ageing is good news insofar as it reflects improvements in both population health and life expectancy. A person born in the mid 1980s has, on average, a life expectancy that is 2 years longer than someone born in 1960 (Statistics NZ 2019).

We are only at the beginning of a long period of population ageing.

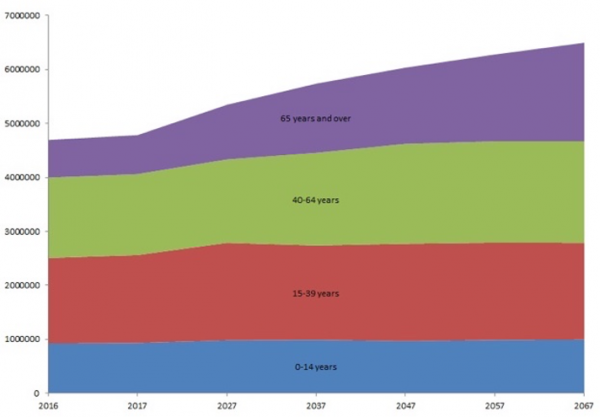

It is important to note that this change is going to happen gradually over the next 40 years as shown in the graph below. While there will be more older people, we are likely to continue seeing a growth in numbers of people aged 40-64 over time as well.

While the population is ageing, the actual number of people aged under 65 years old will also continue to grow, albeit at a much slower pace, as illustrated in the figure below.

Longer term population ageing in NZ

---

[i] NZSAR. (2010, March 22). Workshop for People who Wander. Retrieved October 3, 2017, from http://nzsar.govt.nz/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rq0OTTJWgfk%3D&portalid=4

[ii] Water Safety NZ. Water Safety Sector Environmental Scan. Water Safety NZ, Sept. 2017.

Dementia rates are rising

The ageing population is likely to continue driving more dementia, which may add to demand for searches and rescues unless effective preventative action is taken.

Already, statistics suggest that more than 1 in 5 land searches currently involve people with dementia or other impairment (Lawrence 2019). As one Senior Constable put it recently:

“Back in the first days when I joined, most of our searches were people getting lost in the bush. But with GPS now, those bush searches are reducing, but because we have an ageing population, it’s changed to the elderly going missing.” (Lawrence 2019)

The Ministry of Health has estimated an increase from 50,000 people with dementia to 78,000 by 2026 (Ministry of Health 2014). Alzheimer’s NZ has also developed the projections out to 2050 suggesting solid ongoing growth in dementia for the next 30 years. Of course, such projections need to be treated with caution, given that they exclude consideration of possible future advances in the prevention and treatment of dementia.

People with dementia are much more likely to be involved in ‘wandering’ incidents, whereby disoriented people leave places of safety and don’t necessarily know how to return home.

Most of those who wander go missing from either their homes or rest homes (Halton 2010).

Wanderer incidents were steady at around 23% of category 1 land incidents each year between 2010/11 and 2017/18 (LandSAR New Zealand 2019).

Consequently, we can expect demand from under 65-year olds to expand as well as demand from the over-65 cohort. In other words, despite the ageing population, we cannot expect demand to fall.

Instead, we might expect the growth in demand due to population growth to be mitigated a little by the greater proportion over 65 years old.

The SAR sector is working to prevent wandering

LandSAR NZ is leading the implementation of the Wander Framework to respond to the expected increase in people wandering away and getting lost in the outdoors.

A particularly challenging part of this problem is dealing with the potential for wandering before it occurs. LandSAR are confident that in the future, “new technologies, whilst not preventing wandering, will change the response from emergency to routine, and give greater surety of outcome.

Some of this technology will be sufficiently cheap and unobtrusive, that it will become a more realistic precautionary measure for families who are concerned about the increasing vulnerability of a loved one.”[i] More detail on the benefits and constraints around such technologies is provided in the section on technology (see ‘improved location technology’).

---

[i] LandSAR (2017). Feedback on the draft NZSAR environmental scan, received via email, 23 November 2017, 8.26AM.

The impact of more older people on SAR demand

It’s not entirely clear what impact the increased proportion of 65+ year olds will have overall. It depends on both how active older New Zealanders are in future, and the extent to which they engage in risky outdoor activity.

We know that older people have generally tended, until now, to be less active than younger people. For example, Ministry of Health data suggests that:

- adults aged 65 years and over are more likely to be sedentary than those under 65 years

- adults aged 75 years and over are less likely to be physically active than those under 75 years.[i]

As an example, we know that between 80-90% of the recreational boating population is aged under 65 years old[ii]. Consequently, as we have a large shift of the population into the 65+ category, we might predict less demand for SAR from recreational boaters. We also know that participation in higher risk activity generally declines once people pass the age of 65.

However, we can’t assume that past trends will necessarily predict the future in relation to the ageing population. It may be that future 65+ year olds are both more active and participate in riskier/more adventurous outdoor activity than previous ones. As one participant in a feedback workshop for this environmental scan put it “70 is the new 40”. For example, we know that government communications, the media and social media are all providing strong messages to the community emphasising the importance of staying active as we age for both longevity and quality of life reasons.

Healthier lifestyles and medical advances could also enable older people to stay active much longer in future. As just one example, the development of ‘e-bikes’ or electric bicycles, gives older people the opportunity to cycle and “conquer hills with ease” through a motor integrated into the bike. Furthermore, greater wealth may be giving older people better access to equipment and technology (e.g. personal locator beacons, satellite communicators).

There are some signs that older people are already getting more active. For example, a recent Sport NZ survey found that more than three quarters of New Zealanders aged 65 – 74 years take part in sport or recreation each year[iii]. Similarly, LandSAR report that they are seeing more older people, “particularly in ‘moderate’ wilderness areas (i.e. not extremely rugged backcountry, but well away from road ends, usually on tracks)”.[iv]

While clearly staying fit and active while ageing is a good thing, LandSAR note that the total number of active older people (particularly those engaging in slightly more risky / adventurous activity than previous generations) could result in more slips, trips and medical flare ups when undertaking backcountry activities. In fact, they comment that they are already starting to see such events reflected in the SAROP statistics. For example, statistics from the Mountain Safety Council show that while over 65 year olds represent 5% of those participating outdoors on land, they represent 7% of all injuries and 8% of all those involved in SAROPs.[v] By contrast, 35-49 year olds were less likely to be involved in a search and rescue. [vi]