Who do we help?

Page updated: 11 December 2020

This section provides an overview of who benefits from search and rescue operations and where these operations tend to take place. It also explains how demand for search and rescue changes (or more to the point, usually doesn't) over time.

Where do search and rescue operations (SAROPs) take place?

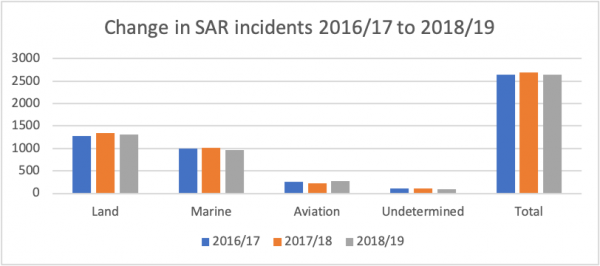

The figure below shows that there are generally more SAR operations driven by land and sea situations, than by aviation problems.

It is also suggests that in ‘normal’ (i.e. non-COVID-19) times, demand is pretty stable over time.

(NZSAR, 2018)

Demand for SAR on land

In their publication “There and Back”, the Mountain Safety Council (MSC) have comprehensively analysed the key factors driving demand for search and rescue operations on land. Some of the key insights from their analysis are listed at the bottom of this section.

Key point: Falling while in remote areas, drowning while crossing a river, and getting freezing cold are the most dangerous things to happen to most people in the outdoors!

The most dangerous places were in the south island (when measured by fatality), but the highest rate of people needing search and rescue is in the central north island (Ruapehu and the Taupo districts).

It is particularly telling that in this area, 80% of the search and rescue operations involved only one person (which suggests it’s best to always participate outdoors with a friend!). The same trend applies in Queenstown-Lakes with 82% of the search and rescues involving one person. However, there is a much higher fatality rate there, with 15 people dying there between July 2007 and December 2014, of which 13 were due to falling.

- on average, there were 540 land-based search and rescue operations annually (over a 5-year period), but this has fallen from 584 in 2012-13 to 490 in 2014-15;

- of the 540 SAROPs, 138 were for trampers, 117 for hunters, 37 for mountaineers, 34 for mountain bikers and 13 for trail runners;

- the central north island had the highest number of people involved in search and rescues – it had 10 times the average number of people involved in search and rescues;

- however 71% of fatalities were in the south island, with the highest number of fatalities while out tramping in Queenstown-Lakes and Tasman;

- 51% of fatalities were due to falling, 14% due to firearms incidents, 14% due to water crossings and 7% due to hypothermia;

- 84% of fatalities were male and 73% were from New Zealand as opposed to overseas;

- only 28% of search and rescues were for two or more people.[i]

---

[i] “Mountain Safety Council New Zealand — There and Back.” Mountain Safety Council New Zealand, 1 July 2016, www.mountainsafety.org.nz/insights/there-and-back/.

Demand across the Pacific

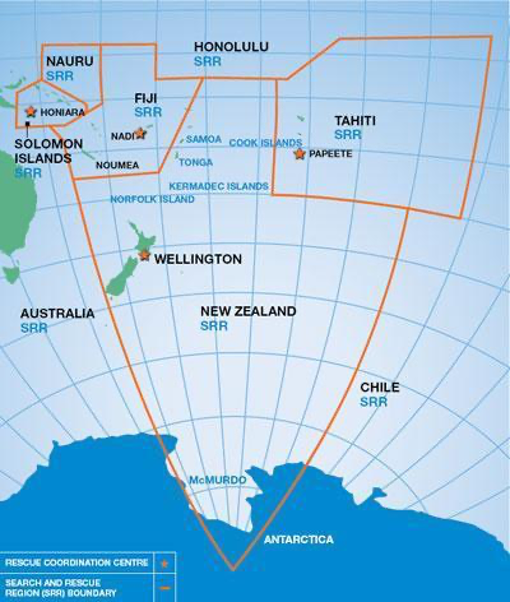

In addition to its work close to the New Zealand mainland, significant effort is put into both coordinating and often directly providing search and rescue across the broader NZ Search and Rescue region. This region stretches all the way from Antarctica to the Pacific Islands.

The vastness of the Search and Rescue Region is illustrated in the diagram below. The sheer size of the Pacific Ocean makes it an enormous challenge to provide search and rescue across the region.

A map of the NZ Search and Rescue Region

While we talk of this as a ‘region’, in fact it spans multiple jurisdictions, each with their own particular local characteristics and challenges. Some jurisdictions involve many small and remote islands with their own obligations and sovereignty. Others have very few search and rescue assets available. Still others run aircraft and ferries that might not be maintained or meet what might be considered ‘reasonable’ safety standards.

There are also different perceptions around the level of safety needed to run a business in different places. For example, one anonymous ferry owner in a Pacific Islands admitted to keeping his lifejackets in a hold under cargo to avoid people stealing them (while meeting the technical requirement to carry them). Another is a ferry operator who regularly picked up new crew for each voyage, none of whom had training in how to operate in an emergency.

It is recognised that the maritime safety culture across the pacific needs to improve. It is in this diverse and challenging context that RCCNZ must often coordinate the search and rescue operations illustrated with red ‘dots’ below. Examples include the Princess Ashika sinking in Tonga and a ferry sinking in Kiribati in 2009.

Demand over the longer term

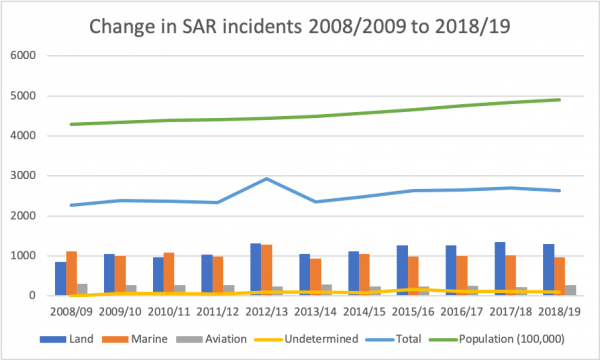

We can learn more by looking at how demand has changed over a longer timeframe.

Extending the time series back ten years, we can see that the total number of SAR operations has mostly slowly tracked upwards in line with population growth.

(NZSAR Annual reports 2008/09 – 2018/19)

While demand has grown at a relatively stable rate over the last 10 years, it is important to avoid so-called ‘straight line extrapolation’ about the future.

As COVID-19 has demonstrated well, it is unwise to simply place a ruler on the trend lines and assume they will continue. This is the case, even when there is no pandemic occuring.

The first reason is that the link between population growth and growth in participation outdoors may weaken in future. For example, changing age, ethnic composition and attitudes may also impact on the link between population growth, participation outdoors and ultimately the need for search and rescue. Secondly, some of the contributors to SAR demand are endogenous; i.e. people can influence them through mechanisms like safety and prevention campaigns, which we hope will reduce the need for searches and rescues over time.

In the February 2020 scan, we noted that some of the exogenous factors, such as climate change and technological innovation, are characterised by exponential or sudden step-changes, both of which could easily disrupt the slow and steady growth in demand to date. We also noted that major events such as wars, storms and asteroids happen and could create unforeseen impacts that disrupt historic trends. This was a month before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic.