Demography and volunteering

Page updated: 29 December 2020

The main section on demography in this scan highlighted a few key trends, all of which are likely to impact on volunteering.

In particular, it is clear that the population is continuing to age and becoming more ethnically diverse and more female (since females tend to outlive males).

It is also clear that while people participate in the outdoors all across the country, the population is becoming more urban.

But what do these changes mean for the future of volunteering in the search and rescue sector?

Urbanisation may challenge the current recruitment model

As mentioned in the section on urbanisation, Statistics NZ population projections suggest that high growth urban areas will continue to experience more growth, while secondary urban areas and rural areas are likely to stay still or keep declining.

This urbanisation means that people increasingly live and work in urban areas while undertaking recreation activities outside them. By contrast, searches and rescues are conducted all around New Zealand and across the wider Pacific region.

Coastguard, SLSNZ and LandSAR are structured around a federated model run by local communities. This model arguably “enables each local group to be autonomous, which fosters a culture of independence and alignment with local communities” (Volunteering New Zealand 2019). However, the sustainability of the model, particularly for smaller rural communities, may increasingly come into question in the face of ongoing urbanisation.

In particular, it appears likely that certain smaller, and economically-declining areas may find it increasingly difficult to find enough volunteers to meet local SAR demand (which continues to be fairly uniformly distributed around the country). Areas that are likely to come under particular pressure include places where there is currently negative economic growth like Rotorua, Whanganui, Greymouth, Timaru and Whakatane, Bulls and Opunake. Where there is negative economic growth, it is likely to become harder to attract and retain volunteers.

In order to track the changing patterns of volunteering, and mitigate any emerging risks, it may be worth SAR agencies collecting and reporting on changes in its volunteering needs versus capacity, both locally and nationally. This will help the sector quickly identify whether a divide between urban and rural settings is emerging and enable a whole-sector response to the challenge.

The need to co-ordinate across different parts of the country, and different parts of the SAR sector, is likely to grow as a result of urbanisation. It is therefore encouraging to see the latest results of a Volunteering NZ study highlighting that there has been a considerable improvement in collaboration across the sector since 2010 and many examples of agencies working together to ensure the safety of their communities.

“Among these examples were Coastguard, Surf Lifesaving NZ and the Maritime Operations Centre combining forces to develop a shared national digital communications platform; and Coastguard representatives sitting on the committee of LandSAR Wanaka.” (New Zealand Search and Rescue 2018)

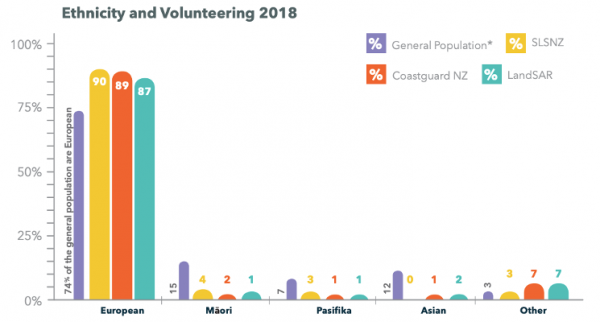

The sector still relies heavily on white, middle-aged men

The SAR sector as a whole does not reflect the diversity of New Zealand.

As at 2019, 76% of the SAR volunteer population was still male and aged over 40 (Volunteering New Zealand 2019). As the manager of the NZSAR Secretariat, Duncan Ferner, has observed:

“Our volunteering demographic (mostly men aged 40+) does not match the demographic of the increasingly diverse communities being sourced for volunteers.” (New Zealand Search and Rescue 2019)

As identified in the 2017 scan, the main exception to this is still Surf Lifesaving NZ, which has nearly equal numbers of male and female members, and 60% of whom are 19 years old or younger (Surf Lifesaving NZ 2019).

So, has the sector become any more ‘reflective of NZ society’ in the last few years? In short, no. A recent report has highlighted that there remains a mismatch between those who currently volunteer in the SAR sector and the diverse face of New Zealand (Volunteering New Zealand 2019).

Quite apart from embracing ethnic diversity, even encouraging more women to volunteer remains a real challenge for the sector. For example, one recent report suggested that there has only been a 4% increase in female volunteers between 2010 and 2018 (Volunteering New Zealand 2019).

Could the SAR sector run out of volunteers?

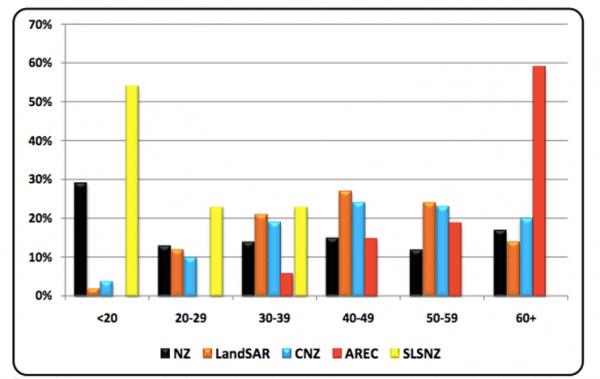

The New Zealand SAR sector is heavily reliant on males, two thirds of whom are aged over 40 years. Could this be a problem for the volunteer pool of people who are available to deliver services in future?

The exception to this ‘older male’ volunteer profile is Surf Life Saving NZ, which has a significant amount of younger and female volunteers and the amateur radio Emergency Communications (AREC) volunteers who tend to be 60+ years old. This is illustrated by the figure below.

NZSAR Volunteers by Area and age[i]

Could we run out of certain SAR volunteers due to lack of age and ethnic diversity? Probably not...

One particular risk arising from the age profile below is that, as the NZ population ages, there may be fewer available amateur radio participants. It also raises the broader question around what the NZSAR sector’s strategy is for replacing and supporting older volunteers – based on the figure below, these appears to be questions for LandSAR, CoastGuard and AREC in particular.

While little progress on embracing diversity appears to have happened in the last few years, should SAR agencies even worry about this? One possible concern is that, unless it becomes more representative, the SAR sector will find it harder and harder to get volunteers. Indeed, Volunteering NZ has asserted this, saying:

“Deciding not to engage and reduce barriers to participation for other ethnic groups means that your pool of potential volunteers will get smaller and smaller, not to mention the skills and experience the sector is missing out on.” (Volunteering New Zealand 2019)

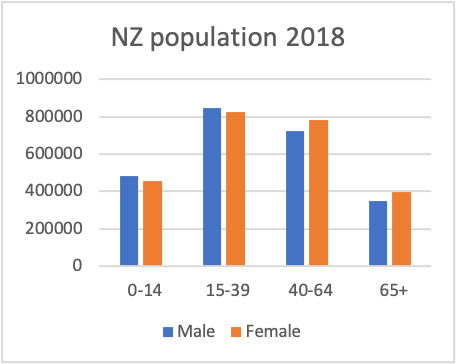

But is this assertion – that the pool of potential volunteers will shrink – actually valid? The data gathered as part of this environmental scan suggests not. In aggregate number terms, the NZ population overall, and even the number of people who fit the ‘traditional’ SAR recruit (Middle-aged, NZ European men), is increasing, not shrinking.

Furthermore, feedback from those working in the SAR sector has not concluded that there was a universal lack of volunteers across the country at present. Instead, some of those with whom we spoke even went so far as to comment that they had more volunteers than they needed and insufficient demand was deterring some volunteers from keeping their skills current.

We also noted that there seemed to be an emerging ‘mixed picture’, whereby urban areas had strong or even oversubscribed volunteer groups, in contrast with areas with shrinking populations and local economies. Overall, as observed in the section on the economy above, continued urbanisation appears to be continuing this trend (albeit gradually).

For example, a 2009 study of volunteering across the SAR sector noted that the main urban areas do have strong and generally large, or oversubscribed, volunteer groups. Other strong groups are located in areas where there is a significant amount of SAR activity; notable examples are the Tasman District and Wanaka. By contrast, it noted that volunteer groups that face issues caused by population problems are generally in the smaller rural population areas with low levels of SAR activity.[i]

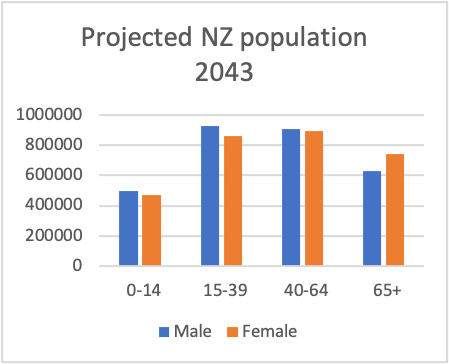

Looking ahead, population projections suggest that there will be plenty of people fitting the existing typical profile of a search and rescue volunteer (at least in highly populated areas) over the next 20 years. The number of 40-64 year olds is projected to increase from around 1.5 million to around 1.8 million and the number of males in this age bracket will increase from around 725,000 to around 900,000. In short, we are not going to run out of middle-aged and older men in urban areas any time soon.

In addition, the numbers of people aged 20-39 is also likely to stay stable over the next 20-30 years. In other words, we don’t need to worry about suddenly running out of young people due to population ageing either.

---

[i] NZSAR Secretariat. (July 2010). Volunteer Study: An Overview of the Voluntary Segment of the SAR Sector, Wellington, New Zealand

---

[i] NZSAR Secretariat. (July 2010). Volunteer Study: An Overview of the Voluntary Segment of the SAR Sector, Wellington, New Zealand

The SAR sector needs to diversify

Of course, simply having a lot of prime-aged people around does not necessarily guarantee they will have either the time or inclination to volunteer. Volunteering for any organisation depends both on what people find interesting or relevant, but also the amount of time they have available.

For example, changes in family formation and care arrangements can have a major impact on how much free time people have available.

There is growing evidence that Millennials are more likely to either stay living at their parents’ house, or to return home after a few years. A recent survey of almost 450 New Zealand parents showed 21% of respondents had one or more millennial children currently living at home, with another 12% saying one could return “any time” (Stephenson 2019).

From 1996 to 2013, the number of people in multi-generational householders grew by 49%, to 496,383 (BRANZ 2016). Reasons for this shift, which has mirrored that occurring in both the USA and UK, included for example:

- saving for a house or travel;

- lack of affordable rental accommodation;

- mental health issues; and

- needing help with childcare.

It appears that this so-called ‘failure to launch’ is then feeding into decisions to get married and have babies later (Statistics NZ 2019). Then, even once they have babies, many women are now generally returning to the workforce faster than in previous generations.

|

“Our volunteers are mostly mums/parents and it seems difficult to get people involved – mainly I think to more mums going back to work sooner after having kids – there is just no time for anything else.” (Volunteering NZ 2017) |

The delay in family formation and increased prevalence of multi-generational living arrangements (particularly where younger family members are caring for older ones) are likely to have a big impact on the time people have available for volunteering. For example, they mean that many of the kinds of people who used to be in a position to volunteer in their mid-40s are now often still occupied with full time parenting duties. Similarly, others who may have had more time available to volunteer in middle age are increasingly finding their time occupied with caring for their ageing parents, who are now living longer than previous generations.

|

“We find the young and the elderly give their time generously, but the middle aged have nothing extra to give” (Volunteering NZ 2017) |

A diverse workforce offers better ability to cope with rapid changes

A further possible rationale for working towards a more representative sector is that it may significantly improve the SAR sector’s ability to deal with a rapidly-evolving environment.

There is research (Syed 2019) to suggest that tackling complex challenges demands more than just intelligence and skill; it also demands cognitive diversity. The question this raises is whether having a greater diversity of people (e.g. different ages, ethnicities, gender etc) can and will provide such cognitive diversity.

Furthermore, not all problems are complex. Sometimes problems need creative solutions, while other times we just need to apply best practice. The fact that creative problem-solving is not always required is why SAR agencies have best practice and SAR response guidelines in the first place.

Of course, even operationally there may be certain circumstances where creative team problem-solving is required. However, more often exploring options creatively relates to the strategic and long term planning requirements rather than operational ones. For example, there may well be value in bringing together diverse parts of the SAR sector and different perspectives (ages, ethnicities, disabilities etc) to consider how best to tackle the strategic challenges identified in this environmental scan. However, there is less likely to be value in brainstorming different possible ways to helicopter a person off a cliff or to pluck someone out of the ocean when faced with real time pressure.

Older people, women without children, and people with disabilities are under-tapped

While changes to family formation trends and living arrangements mean that some people have less time available to volunteer than in the past, others have more. This could actually provide opportunities to boost volunteer numbers in future.

For example, across the NZ population, fewer women are having children and these people may have more time available to volunteer if they can be attracted to do so.

Similarly, the number of older people (both male and female) leaving the workforce, may offer a significant 10-20 year boost to volunteer numbers if they can be attracted. Women tend to live longer than men, which is gradually being reflected in the relative proportions of each gender as the population ages. As demonstrated in the graphs below, there will be significantly more women than men aged 65+ by 2043.

(Statistics NZ 2019)

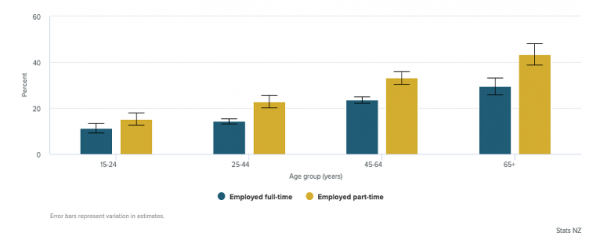

Older people, women, and those less attached to the workforce are typically more likely to volunteer, as demonstrated below. This opportunity may be offset to some extent by the fact that much SAR voluntary activity requires people to take a certain amount of personal risk (e.g. rescuing people off cliff faces or other high risk areas). However for people wanting to be engaged in ‘healthy ageing’ there may be significant and mutually beneficial opportunities through tapping into this population.

NZ volunteer rates by work status, June 2018 quarter (Statistics NZ, 2018)

While there is a positive association between age and disability, there is every reason to believe that many search and rescue functions could be undertaken by people aged over 65, in the medium term. A key question will be how to attract, and best support, this potentially enthusiastic volunteer workforce.

|

“Volunteering has become increasingly the role of older Kiwis... time and financial pressures prohibit younger people from stepping up.” (Volunteering NZ 2017) |

In fact, giving people with disabilities more responsibility in the search and rescue sector (and helping them to take on challenging new roles) is likely a win-win for both parties. This was recently emphasised in the government’s Health and Disability Review report, which said:

“Boosting employment of disabled people overall may be the single biggest contributor to improving the wellbeing of disabled people. Bringing their skills to the workforce in health will also make the sector more responsive, adaptive, inclusive, and reflective of the community.” (Health and Disability System Review 2019)

How to attract a more diverse voluntary workforce

Looking ahead, what should SAR agencies do to attract a more diverse range of people to volunteer? There are several things that may help.

Understand the values different groups hold

One theory is that SAR agencies need to start by better understanding and reflect the different values of different demographic groups. The New Zealand Recreation Association puts this well, saying that we need to “recognise alternative value systems, calls on time and available resources.” (New Zealand Recreation Association 2018)

As an illustration, we know that people from different backgrounds see the value of volunteering differently, so it makes sense to present volunteering in the terms that resound best with different communities. For example, simply looking at the question of ethnic diversity, the quotes below (New Zealand Recreation Association 2018) illustrate just how different the starting assumptions and values of different ethnic groups can be.

“Many immigrants have come to NZ to improve their lives via hard work in business so giving up time to do something without financial reward doesn't make sense to many immigrants.” - Estella Lee (from Chinese Conservation Trust)

“From a Māori perspective, the mountains are our ancient ancestors and to stand on top of them and say you’ve beaten them is disrespectful.” - Dr Ihirangi Heke

Of course, it is important to recognise that values are not just inhibitors to volunteering. On the contrary, they hold the key for attracting a more diverse array of New Zealanders to both participate in the outdoors and volunteer. For example, by tapping into the Māori concepts of whanaungatanga (kinship, relationships), manaakitanga (respect, reverence) and aroha (compassion), it would be very plausible to attract more Māori to volunteer for search and rescue. Similarly, tapping into Pacific concepts around respect and reciprocity, service, spirituality, family and leadership could offer powerful ways to attract Pasifika to volunteer (Massey University 2016).

Part of this involves championing people to lead, drawing on the particular skills, knowledge and perspectives that are unique to them. For example, in working to attract more Māori into active recreation and sport, Sport NZ explicitly focuses on championing “participating and leading as Māori”, rather than just adopting a ‘one size fits all’ approach to inviting participation (KTV Consulting 2017). Similarly, to attract more women, more Māori, more Pasifika and more diverse Asian groups to volunteer in search and rescue, SAR agencies would ideally adopt well-informed, targeted and culturally-relevant strategies of recruitment and retention, rather than adopting a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

It is clear that different volunteer recruitment strategies can and do furnish very different results. For example, Surf Life Saving has been particularly successful at attracting both females and younger people while other parts of the SAR sector have been less so. While there may be certain characteristics of Surf Life Saving that make volunteering in that area more attractive to these demographics, there is some evidence to suggest their success at doing so is at least in part the product of a concerted drive to attract a more diverse group of volunteers. This may mean that there are valuable lessons the rest of the sector may learn from their particular approach.

Champion unity and diversity simultaneously

Simply throwing together different people and expecting spontaneous performance improvement is unrealistic. Instead, research suggest that it’s important to invest in creating cohesive group or team cultures before expecting them to perform well together. This kind of ‘bonding capital” is captured by the quote below.

“Being part of an organisation that not only values search and rescue, but volunteer safety, training, support, crew bonding between all unit members, and being part of one massive family” - Volunteer comment regarding strengths of the SAR sector (Volunteering New Zealand 2019)

However, often people believe that creating a sense of team unity requires ignoring difference or asserting that ‘everybody is the same here’. This is incorrect. As well as so-called ‘bonding capital’ (things that tie people together, another kind of capital is needed to embrace diversity: ‘bridging capital’. This is basically just the idea that we can also embrace difference at the same time as having some group values in common.

Harvard Professor Robert Putnam highlights that it is quite feasible for people to hold multiple identities at once, meaning that people should not be required to repudiate one identity in order to embrace another. The existence of collective identities can even help overcome any divisions between groups of volunteers that might arise. Putnam says:

Experience shows that social divisions can eventually give way to “more encompassing identities” that create a “new, more capacious sense of ‘we’". (Jonas 2007)

So, ideally the SAR sector would look to both create shared group identity (e.g. “being part of the SAR family”), while simultaneously accepting and validating individuality, multiple cultural identities, and any other identity differences.

Take a ‘skills and capabilities’ approach

Above, we identified that there has only been a 4% increase in volunteering rates of women between 2010 and 2018. Might part of the reason for this be that certain parts of the SAR sector are holding either conscious or unconscious beliefs about the capability of women (and possibly older people and people with disabilities) to fulfil certain search and rescue functions? If so, then one of the keys to attract a more diverse workforce is for sector leaders to explicitly repudiate such beliefs.

But why might some in the SAR sector be struggling to adapt to the idea that women, older people and people with disabilities might make valuable volunteers? Some people may have legitimate concerns that nevertheless provide implicit signals to certain demographics that they are not welcome. Indeed, it is easy to provide subtle signals to certain demographics that we do not believe they can fulfil certain roles. For example, even Volunteering NZ has commented that:

“SAR, however, is also a sector in which health and fitness is essential to most volunteer roles so there is an inherent risk in relying on a volunteer workforce that is ageing.” (Volunteering New Zealand 2019)

This comment implicitly suggests that poor or insufficient health and fitness is a necessary characteristic of an older, or at least ageing, workforce. Similar sentiments have been expressed about the capability of women and people with disabilities to work in the Police force or military in the past. Instead, we know that health and fitness tend to vary over population distribution curves. So perhaps it would be more constructive to establish certain health and fitness standards required to fulfil certain voluntary roles and identify the roles that do and don’t require meeting them.

An explicitly skills and capabilities approach would be consistent with the Ministry of Health’s ‘positive ageing’ strategy and the focus of the Ministry for Women, which is aimed at ensuring the contribution of women and girls is valued and that all women and girls can fully participate and thrive. There may also be opportunities for collaboration and joint Budget bids spanning SAR and other parts of government to ensure the SAR workforce of the future is both fit and healthy enough to volunteer, while being included.

As part of this, it is important to recognise that not every voluntary job in the SAR sector requires very high fitness levels. Parts of the SAR sector are clear on this already. For example, Coastguard NZ already explicitly recruits ‘shore crew’, who do not require the level of training and time commitment as ‘wet crew’ operational roles. Surf Life Saving NZ in the Bay of Plenty similarly encourages volunteers to provide support for search and rescue operations in roles like providing provisions and looking after equipment (Volunteering New Zealand 2019). However, just because these role distinctions exist now doesn’t mean they are being actively marketed to diverse sections of the NZ population to diversify it over the long term.

“Skills based volunteers do need induction but not technical training. Please consider the newer types of platforms and changing volunteering trends…Volunteering turnover and lack of training can also be positive signs too!”

Being explicit on different skills and capabilities needed for different jobs (i.e. formalising roles much more) would have the benefit of reducing the need to train some volunteers as intensively, though care would be needed to clarify what constitutes ‘basic’ induction and to specify oversight mechanisms tightly enough to avoid creating new risks. Needless to say, this would mean that the 1/3 of the SAR sector not currently offering an induction programme or training opportunities to volunteers would need to address this rapidly (Volunteering New Zealand 2019). It might also mean considering carefully how much training is really required for volunteers who may only stay for a few months or a year.

To attract more female volunteers, SAR agencies also need to better understand the motivations that drive women, older people and people with disabilities to volunteer. For example, we know that women are often attracted to certain kinds of organisations and not others. Statistics NZ research has suggested that men are most likely to volunteer for sport or recreation organisations (38.7 percent), while women are more likely to volunteer for religious or spiritual organisations. The same research found that women were more likely to volunteer for health, social services, and education or research type organisations. This raises questions around how well the SAR sector understands what motivates women to volunteer, and how organisational culture may be playing a part.

Taking a more personalised approach for matching volunteers with tasks could prove a ‘win-win’ for both the SAR sector and for diverse volunteers. Of course, appropriate fitness tests and training is necessary to perform certain functions, but we must remember that to meet current volunteering levels, less than 1% of the NZ population would need to qualify.

Steps in the right direction

While significant ongoing effort is required, it is important not to become too discouraged about the relatively slow progress towards a more diverse SAR workforce.

Workforce reform usually takes time, and the SAR sector is a particularly complex network of organisations.

The NZSAR Secretariat risk matrix shows that good work is already underway to assist SAR agencies to develop and maintain their own volunteer strategies and, as part of this, to focus on “the recruitment, retention and engagement of effective SAR volunteers reflective of NZ Society.” (NZSAR Secretariat 2019). There are also other encouraging signs that the sector is moving in the right direction.

For example, the NZSAR Secretariat has recently begun emphasising the importance of accepting diversity by announcing a set of new guiding principles for valuing volunteers (New Zealand Search and Rescue 2019).These principles broadly advocate inclusiveness, responsiveness to volunteers, open and honest communication and collaboration.

In short, they are useful because they begin to encourage a set of collective identity and joint values, while acknowledging diversity. That said, the principles only represent a start in a much longer journey needed to attract a more representative cross-section of New Zealanders to volunteer.