Key insights - NZSAR in a changing world

Page updated: 19 February 2021

The NZ Search and Rescue (NZSAR) sector is all about saving lives.

However, we are living in a world that is characterised by more volatility, uncertainty, ambiguity and complexity.

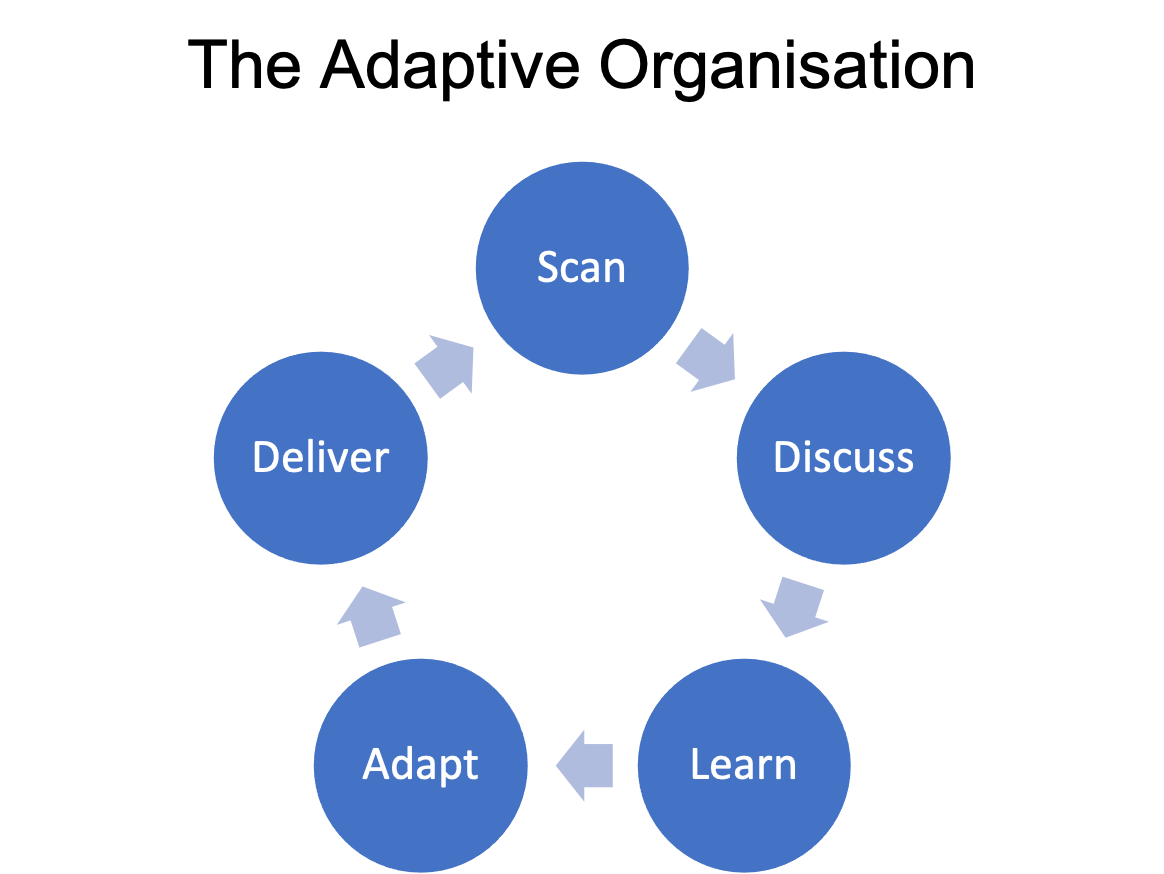

So, to stay effective in a changing world, NZSAR organisations, and the sector as a whole, need to scan the environment, extract the insights, adapt and deliver relevant services. This continuous adaptation process is illustrated by the diagram below.

The aim of this scan is to help NZSAR on its journey of scanning, learning and improving search and rescue services over time.

Resilience and adaptability are key

The key message of this scan is one of change. That change is neither uniform nor perfectly predictable. Thus a mix of both planning and the ability to adapt in real time are key for NZ SAR organisations to stay effective in the future.

With the world-wide impacts of climate change and COVID-19 being felt keenly, it is easy to conclude that change is accelerating in all areas. However, this scan tells a more nuanced story.

The pace of change overall is variable

We have identified at least 3 different kinds of change with which the SAR sector must contend going forward:

1.Gradual changes based on slow-moving but fundamental forces - for example, demographic and economic changes - are generally slow-moving and linear in terms of their rate of change;

2. Exponential changes - these are changes that can lull you into a false sense of complacency because they start slowly, but the pace and extent of change increases rapidly over time - climate change and technological innovation are good examples; and

3. Major disruptive events - these are major events like volcano eruptions, mine collapses, earthquakes or even more concerning, global disruptions like pandemics. They are always possible but can and do disrupt the gradual changes in (1) above.

It is important to understand, plan for, and respond to all 3 of the kinds of change above. However the kind of responsese that are appropriate for each are different.

Also, we note that while trends can give an indication of the way things are headed, as COVID-19 has demonstrated amply, surprises can and do happen.

A particularly useful economic concept comes into play here: that of bounded rationality. It says simply that you cannot make decisions on the basis of information you do not have. Hopefully the following environmental scan update slightly widens the current information base available, while acknowledging that the only real constant is change.

Some change is gradual

On the demographic front, the population is still ageing, women are still outliving men, urbanisation is continuing and we are still becoming more diverse. These changes, while not rapid, do throw up some real strategic challenges for the SAR sector in the medium to longer term.

In particular, they relate to issues such as workforce planning and culture, rather than how to manage immediate spikes in demand.

As one example of this kind of 'gradual' change, since the first version of this environmental scan was conducted in 2007, we have not seen a major change in demand for search and rescue. A ‘glass half full’ view of this is that, while there has been a slight uptick in land- and aviation-based SAR operations, it could hardly be called a ‘spike’. By contrast, a ‘glass half empty’ perspective might be that prevention efforts have so far failed to significantly reduce overall demand either.

Until COVID-19, social trends appeared to be moving somewhat faster than the demographic and economic trends - which were mostly proceeding in a relatively stable and linear manner.

The most notable recent changes appeared to relate to the policy decisions successive recent governments made and the impacts of those decisions on income distribution. For the first time in 5 years, real wages were increasing at the same time as unemployment was falling, and inequality was reducing. While the links to the SAR sector may not be obvious, these changes are particularly relevant for attracting volunteers generally, and particularly for those from diverse and/or deprived backgrounds (two things that unfortunately still correlate quite closely).

More broadly, most New Zealanders have increasingly reported a sense that life is ‘moving faster’ and therefore people were feeling under time pressure (so had less time for things like outdoor recreation and volunteering).

The other major social trend explored was related to attitudes when people venture into the outdoors. There is some evidence that SAR partners’ efforts to raise awareness are working: people are more prepared when venturing outdoors in some respects. However, the fact that some people still stubbornly refuse to pack life jackets when going boating or to prepare properly before going tramping, suggests that there is still work to do in this area. Furthermore, raising awareness should only be seen as part of an overall behaviour change strategy. There may yet be room to systematically consider necessary changes to laws, regulations and enforcement to complement awareness-raising efforts.

Of course, just because some change is gradual and ongoing does not make it inevitable that it will continue. Economic growth, tourism and the expansion of the marine economy were all continuing until COVID-19 hit.

Even gradual change can have major implications

Certain environmental factors, particularly relating to demography - things like ethnic make up and ageing - move much more slowly than others (such as technological change). However, just because they are gradual does not make them unimportant. Quite the opposite - because we tend not to notice gradual change, we need to make a special effort to adapt to them.

We explored the potential impacts of the gradual changes to demography, the economy and social trends on volunteering and concluded that several demographic trends are likely to have a significant ongoing impact on the SAR sector’s ability to recruit and retain volunteers. These were:

- population growth, driven by ongoing immigration (both a contributor to demand for search and rescue, and possible SAR volunteers if diversity is tapped appropriately);

- population ageing and increased disability rates (affecting the physical capabilities of some volunteers, but also offering a source of potential new volunteers);

- ongoing urbanisation, leading to ‘hollowing out’ of some rural areas (potentially putting strain on a purely locally-led model of volunteering over time); and

- people feeling increasingly time poor and choosing to spend less time outdoors (which could both reduce demand for search and rescue, but also make it harder to attract volunteers).

On the up side, it appears that there is no immediate volunteering crisis for the SAR sector. In particular, many of the demographic trends described above will continue to occur gradually.

This said, just because some trends are gradual does not mean no immediate action is required. Quite the opposite - in fact perhaps we should be planning our workforce much more, particularly using scenario thinking, to ensure the workforce of the future matches the needs of the future.

Furthermore - given the exponential nature of many environmental changes afoot now, and the increased likelihood of shocks - early planning and taking steps to build workforce resilience are key. This particularly applies to the challenge around getting a more diverse and representative SAR workforce and ensuring it is sufficient as the environment continues to evolve.

Investing to attract a more diverse workforce may also help the SAR sector to navigate an environment that is increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. This is because having more diverse thinkers can enable a step-change in an organisation’s or network’s strategic thinking ability and adaptability. However, to realise this significant strategic benefit, the SAR sector will need to actively welcome new perspectives and skills, and be open to doing things differently.

Of course, before it can benefit from the new perspectives of diverse volunteers, the SAR sector needs to actually attract them. People tend not to volunteer for activities that are irrelevant to their lives; so promoting outdoor participation and volunteering for SAR are likely to be highly complementary activities.

Also, attracting new kinds of volunteers will require work to understand the differing values and priorities of different generations, genders and ethnic groups. It will also mean pitching the value proposition or ‘offering’ around volunteering to each demographic in a way that resounds authentically with each.

Some questions SAR agencies may wish to explore as part of trying to attract a more diverse volunteer workforce include:

- What SMART[1] commitments to action might each agency (and/or the sector as a whole) usefully make in relation to securing a volunteer workforce that better reflects New Zealand?

- What does the SAR sector need to know about the demographic groups who do not usually volunteer for the SAR sector (e.g. the values of different ethnic groups, older people, women etc) in order to attract and retain them better in future?

- How might the SAR sector ensure that there are sufficient numbers of volunteers all across NZ, as certain local areas face population decline?

In this scan, we also observed that there does appear to be an increased preference for shorter-term and episodic volunteering, particularly among younger generations. This seems to be driven by a combination of factors: people seem to feel they are juggling more priorities, are more economically-stretched and have a much greater array of options for filling their free time enjoyably. This suggests that the challenge around attracting people to participate in the outdoors, and to volunteer in the SAR sector, may well be two sides of the same coin. It is also notable that non-NZ Europeans are both less likely to participate in the outdoors and to volunteer for SAR agencies at present (might these things be linked?)

However, available data (particularly from overseas) did not suggest that a decline in volunteering, including for the SAR sector, is inevitable. A targeted and personalised approach to recruiting new volunteers will likely be the best way to attract and retain a diverse workforce. This approach will need compelling answers to the following kinds of questions for potential recruits:

- Why should I care about search and rescue – why would my decision to volunteer for this sector make a real difference in the world?

- What will I (and/or my community) get out of volunteering for the SAR sector? (e.g. training/qualifications/skills, new friends, life satisfaction, recognition etc)?

How much of my time (e.g. per week) will be needed when I volunteer, and how easy will it be to juggle volunteering for SAR with other commitments?

---

[1] Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound.

Our world is ever more connected

On February 14, 1990, while on its way out of the Solar System, Voyager I turned around to take a photo of Earth in the vastness of space. The photo, shown below, was the subject of a speech by Carl Sagan, famously called the 'pale blue dot'. The speech emphasised just how inter-connected and inter-dependent all humans on earth are.

Globalisation has shunk the world, increasing our inter-dependence. For example, both the rapid global spread of COVID-19, and the vaccines against it, are bi-products of a more inter-connected world. Climate change is similarly a product of a world where the human impact on the planet is more than any single city or nation. Responding effectively in this context is also likely to require more inter-connectedness.

Whether we like it or not, as humans living on earth, we are all inextricably a part of our environment. We no longer live as separate tribes scattered across the earth. We live in a time when a virus that pops up in one place can spread across the globe in a matter of weeks. We live in a time when climate change affects every single living organism on our planet.

To run organisations or networks like NZ SAR effectively in this context, we must try to understand our inter-connected world to support the right strategic and operational decisions.

This connectedness is driving faster change

The fact that we are more connected is driving more change in our world, and the pace of that change is picking up as well. This environmental scan has highlighted and explored 3 main areas where the pace of global change is likely to have significant impacts on the SAR sector.

These key global change areas are:

- COVID-19

- Climate change

- Rapid technological improvement.

We have already canvassed the impacts of COVID-19 and these impacts will continue to reveal themselves over the coming years until the virus is either eliminated or brought under sufficient control globally to enable life to start resembling normality again.

The news on the environmental front since the last scan is less positive. While the world is increasingly understanding the reality of climate change, progress to actually curtail it appears to be well short of what is needed to avoid global temperatures increasing. Even worse, the future projections in terms of sea level rise and extreme weather events due to this warming are getting ever more dire. This is likely to drive higher demand for search and rescue (possibly exponentially more) in the medium to long term, including for mass rescue.

This update also explored the question of whether anything had notably changed in terms of relevant technology in the 5 years since the first scan in 2021. The pace of technological change is continuing to accelerate. Without trying to be exhaustive (a hopeless endeavour when it comes to technological change), the scan identified a couple of key trends worth monitoring. For example, better ability to solve the ‘travelling salesman’ problem and developments in artificial intelligence may well offer significant opportunities for speeding up search and rescue in future and improving the chances of success.

Perhaps more challenging than the SAR sector adopting useful new technology itself is working out how to influence the public to adopt helpful technologies. A key part of this is likely to be making it both easy for the public to adopt useful technologies that will help them to be located quickly, and making it less attractive to be blasé about venturing outdoors without a means of being found. In particular, it is likely that ongoing and long-term effort will be needed to convince the public that simply carrying a mobile phone is often insufficient preparation.

Responding to exponential change effectively requires speed

It is clear that we are living in a time of exponential environmental change in certain respects, and certainly when it comes to climate change and the accelerating pace of technological development. These are features of the environment that render the development of rigid annual plans unhelpful because the pace of change is accelerating, making challenges much harder over time.

In this scan, we have highlighted both climate change and technological change as examples of exponential change - i.e. changes that are accelerating over time, to which the SAR sector will need to adapt.

- Climate change will make weather more unpredictable, throwing up more disasters (e.g. storms and floods).

- Rapid technological change has the ability to both prevent the need for, and then speed up SAR responses, but unless technology is upgraded in a timely way, it is easy to miss key windows of opportunity to enjoy improvements in a timely way.

What makes both these kinds of global changes tricky to understand is that the rate of change initially starts slowly, before increasing exponentially faster over time. Exponential change can also speed up the pace of problems and the ability to find solutions to them.

In particular, exponential changes are much easier to deal with effectively if we take action decisively early. The New Zealand response to COVID-19 has highlighted this point clearly - the government has received much praise internationally for spotting the risk of the virus quickly and taking action rapidly to lock down.

Similarly, SAR agencies would be well advised to understand and make plans to deal with the potential for climate change disruption now and to actively and rapidly explore the challenges and opportunities around new technologies highlighted in this scan.

---

[1] 1957 November 15, New York Times, President Draws Planning Moral: Recalls Army Days to Show Value of Preparedness in Time of Crisis by William M. Blair, Quote Page 4, Column 3, New York. (ProQuest), https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/11/18/planning/#note-17261-5, Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Rapid global change means facing shocks more often

Obviously, how well the world, and New Zealand, recover from COVID-19 will be the single biggest driver of both demand for and supply of SAR services in the medium term. However the many other shocks New Zealand has experienced in recent years highlight that we should not be lulled into a false sense of security that shocks will always come one at a time, nor that shocks that have occurred recently will not occur again.

To demonstrate, COVID-19 is a bi-product of our inter-connected globe. This inter-connectedness will remain a feature of our world for the foreseeable future, since individuals, organisations and nations benefit from cooperation and trade enormously. Unfortunately though, this means the same conditions that allowed this pandemic to emerge and ravage the world are still in place globally.

The answer is not to seek to become isolated, but rather to cooperate more to find solutions to global challenges together. This is exactly how multiple effective vaccines to COVID-19 have been developed and shared around the world in record time.

We also need to take the time to understand how shocks impact on demand and supply of SAR services. For example, depending how quickly international travel does (or doesn’t) resume, we could see a complete halt to the hitherto inexorable trends of tourism, immigration and thus increased ethnic diversity and population growth. Among the many down-sides of this halt would be that our economic productivity (and thus our ability to tax and spend on services like SAR) requires a growing population, which relies on this immigration.

All of this means simply that ideally the SAR sector won't just deal with the current shock that is COVID-19, but rather prepare for the inevitable future ones too.

Resilience is the watch word of the future

The SAR sector’s service model has emerged reasonably organically over time, including how it is funded, how volunteers are recruited and trained, and its delivery models. This has worked well to date. However, in an environment of more change and more shocks, a more deliberate approach is needed to both plan ahead and build resilience to respond to inevitable shocks.

This scan suggests that there are particular risks around the search and rescue sector being largely volunteer-based and given the dynamic nature of the New Zealand and general Pacific environment (particularly given climate change).

Consequently, we suggest that there is a need for a deeper assessment of how well the SAR sector will respond if different risks or shocks happen at the same time.

A critical observation is that devolved organisations (like the NZ SAR sector) tend to do well in normal times, but strong command and control structures are better for times of crisis. This does not mean we are proposing a shift to a command and control structure immediately.

However, we strongly recommend the sector consider explicitly how the SAR sector will likely respond when placed under stress – something we think is reasonably likely given the range of drivers emerging that could spike in the next 5-10 years.