Attitudes & preparedness for outdoor recreation

Page updated: 28 December 2020

Another social trend relevant to the SAR sector relates to attitudes regarding participation in the outdoors.

There is plenty of evidence that links attitudes about how to be safe in the outdoors and the number of injuries, fatalities, and demand for search and rescue.

Good prevention and effective training in how to stay safe when in trouble are clearly critical for reducing the demand for SAR.

At present, the level of public preparedness appears to be very mixed, particularly across different environments.

Water safety for boaties

In 2018, over 1,515,500 people took part in recreational boating (Maritime NZ 2019). So, are we getting safer on the water or not?

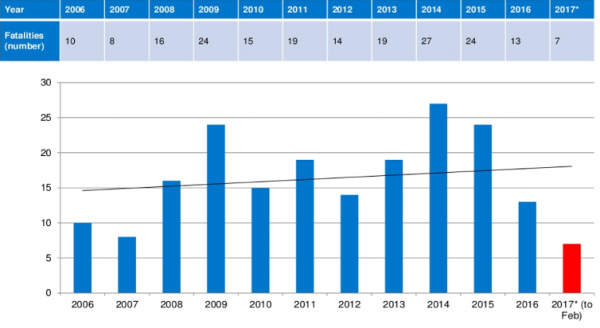

Over the past few years, the recreational boating death toll has dropped from 32 in 2014/15 to 15 in 2018/19 (Maritime NZ 2019). This is a nearly 53 percent reduction in deaths.

So, annual variation notwithstanding[1] (e.g. due to colder or hotter summers), things seem to be improving.

Maritime NZ, 2017

There are also some positive signs that the efforts to ensure people prepare before heading outdoors, carrying the appropriate safety equipment, are beginning to pay off.

For example, as at 31 May 2019, the number of New Zealanders carrying a locator beacon when heading into the wilderness had reached an all-time high, with 114,000 in use nationwide, 87,600 of which were registered with the Rescue Coordination Centre NZ (Maritime NZ 2019).

All this said, further improvements remain possible.

For example, Maritime NZ notes that the majority of the 15 fatalities over 2018/19 might have been avoided if lifejackets had been worn, two forms of waterproof communication were taken to call for help, weather conditions were properly checked before going out, and alcohol consumption was avoided.

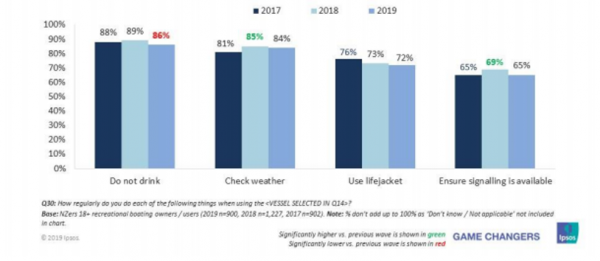

Also, it appears that for many boaties, the safety messages are still not getting through, as illustrated below.

Boaties who don't play it safe, 2017-2019

While there was a decrease in the proportion of non-drinking boaties in 2019 (86% versus 89% in 2018), there was also a decline in boaties who make sure there are at least two ways that they are able to call or signal for help (65% in 2019 versus 69% in 2018).

Weather-checking and lifejacket use have remained stable (Maritime NZ 2019). There has also been little change in the number of boaties who have completed formal boating education courses: just 1 in 5 (Maritime NZ 2019).

Most worryingly, there has been a significant decrease in the number of boaties who say they ensure there are enough lifejackets for all their passengers ‘every time’ (Maritime NZ 2019).

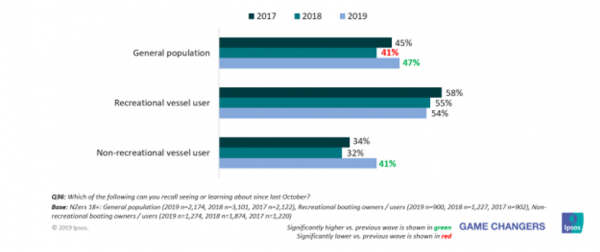

It also appears that while the safety messaging has successfully raised awareness among the general population and non-recreational vessel users, it has not done the same for those actually taking part in recreational boating.

It appears the messaging is not yet getting through to recreational vessel users as effectively as it could.

Recreational boaties not getting safety message yet

---

[1] 19 - 20 boaties, on average, die each year (based on last five years); 19 in 2017, down to 4 in 2018 and 18 so far in 2019 (Maritime NZ 2019)

Water safety for swimmers

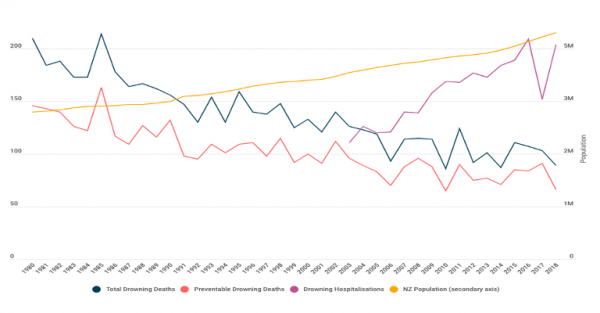

Of course, fatalities in the water do not just happen when people are participating in recreational boating. New Zealand has one of the highest drowning rates in the OECD, most of which relate to swimming.

In 2017 there were 92 preventable deaths involving water (Water Safety NZ 2018).

However, as the graph below highlights, the number of fatal drownings is reducing over time overall, though there is still work to do on reducing near-drowning hospitalisations.

NZ drownings, 1980-2018 (Water Safety NZ, 2018)

Preparedness for adventures on land

In 2017, we also noted that there was considerable room to improve preparedness when people ventured into the outdoors on land. So, have attitudes towards safety on land among the public improved or worsened since then?

It is difficult to answer this question definitively because there does not appear to have been any update or repeat of the 2017 attitudes survey to date.

However, we can gather some data from recent surveys. For example, during 2018, 134 people who were participating in land activities across New Zealand were surveyed across nine sites. The research found that, despite efforts to raise awareness:

- Nearly half of day walkers did not leave intentions about their trip;

- Only 13% of respondents were carrying distress beacons; and

- There was little difference in general equipment carried between those who were in poor weather compared to those in fair weather.

Interestingly, there may be a difference between what people know they should do to prepare and what they actually do.

For example, in one survey, although many people thought it was their responsibility to carry a beacon when walking and hiking in New Zealand’s wilderness, they were not actually carrying a beacon on the trip they were doing[i]

NZSAR Secretariat analysis suggests that the increase in category 2 land incidents has been, at least in part, driven by the increase in Personal Locator Beacons (PLB) that have been registered with RCCNZ[iv]. Their analysis also shows that 69% of the category 2 alerts are for people participating in tramping, hunting, or outdoor sports related activities (matters that would previously have been dealt with by the NZ Police as category 1 incidents). The rise in the category 1 demand appears to be driven by an increase in wandering activity.

What can we conclude from all of this data? Perhaps that significant further reductions in fatalities could be achieved if those involved made better assessments of how dangerous the environment was and their own relative capabilities.

This might indicate the need for more targeted social marketing campaigns to raise awareness that a ‘she’ll be right’ attitude is likely to significantly increase the odds of dying while outdoors.

Of course, this is already the tenor of many existing campaigns by various SAR agencies, so perhaps this simply confirms that existing awareness campaigns and enforcement efforts are on the right track.

---

[i] NZSAR Annual Report 2015-16. New Zealand Search and Rescue Council, nzsar.govt.nz/annual-report.

[ii] NZSAR. outdoor safety summary. Retrieved October 3, 2017, from http://nzsar.govt.nz/Portals/4/Publications/Research/OUTDOOR%20Attitudes%20_%20Knowledge%20Research%20Report%20Aug%202015.pdf

[iii] Otago University. “Centre for Recreational Research.” Http://Www.cmnzl.co.nz/, www.cmnzl.co.nz/assets/sm/6288/61/15301BrentLovelock.pdf.

[iv] "New Zealand Search and Rescue Council." 21 Sep. 2016, http://nzsar.govt.nz/Portals/4/Publications/NZSAR%20Council%20Meeting%20Minutes/NZSAR%20Council%20meeting%2021%20September%202016%20combined%20documents.pdf. Accessed 4 Oct. 2017.

Do kiwis or foreigners prepare better for the outdoors?

In reality, neither New Zealanders nor foreigners stand out as being excellent in preparing for the outdoors. Foreigners tend to under-estimate New Zealand's particular conditions and kiwis tend to suffer from sometimes-fatal over-confidence.

New Zealanders are often over-confident when venturing outdoors

There is also no sense that New Zealanders were any better than foreigners when it came to being prepared.

In a survey, only 45 per cent of New Zealanders surveyed brought enough food for emergencies with them on an outdoor trip, and only 56 per cent brought a warm hat with them on an outdoor trip.[ii]

Possibly exacerbating this situation is the fact that club membership has fallen through the floor. Now only around 8% of New Zealanders are part of a club[iii]. Clubs typically provide a measure of guidance on how to deal with outdoor situations – guidance that would be missing if people ‘go it alone’.

NZSAR sector participants refer to a phenomenon they call ‘recreational ‘snacking’ – whereby more people engage in certain outdoor activity with no real expertise in any particular form of recreation.

It is also possible to extract a couple of useful insights from other trend data. For example, the vast majority of fatalities in 2017 occurred on ‘advanced’ or ‘expert’ walking tracks, or ‘off track’.

Furthermore, a disproportionate number (44%) of fatalities happened when people were either solo tramping or had been separated from their group.

Men were found to be more than twice as likely to be killed when tramping than women. Perhaps most tellingly, three quarters of fatalities were caused by either falling or drowning, with hypothermia being the next biggest cause (Mountain Safety Council 2018).

By contrast, foreigners often don't understand NZ conditions

Recent research has suggested that people coming to NZ from overseas do not understand how quickly weather can change here. It found that while a majority (74 per cent) of New Zealanders strongly agree you should plan for and expect weather changes in New Zealand, slightly less than half (48 per cent) of international tourists gave the same response[i].

Furthermore, international tourists were less likely than New Zealanders to bring clothing for all possible weather, enough food for the trip and sunscreen on outdoor trips.

By contrast, advice on how to stay safe more generally appears to get better traction with people from overseas than kiwis[ii].