How do we work?

Page updated: 24 December 2020

We help save lives in a number of ways:

Our prevention activities

A wide range of SAR agencies undertake prevention activities, in an attempt to minimise the need for SAR services or reduce the impact of an incident should it occur.

A simple, nationally-led framework, has been developed for all stakeholders to use to complement existing environment-specific strategies, such as the ‘Water Safety Sector Strategy 2020’.

The NZSAR Secretariat is now structuring a number of initiatives based on the framework to:

- enable a greater collective understanding of the prevention activities underway across New Zealand;

- add to existing research around the behaviour of people recreating; and

- connect and support effective prevention responses.

Those initiatives are likely to result in an overall picture of the prevention landscape, which will ultimately be available from the NZSAR Secretariat. Consequently, this environmental scan does not seek to duplicate that work. That said, it is acknowledged that prevention activity, and the relative investment in prevention versus search and rescue activity, has a significant potential impact on future demand.

A prevention deep dive: Wandering

Prevention activity is often most effective when it relates to slow-moving changes and challenges. One such challenge is the rising incidence of dementia in the population.

“Dementia” is an umbrella term used to describe a group of diseases that cause physical changes and damage to the brain. Causes include Alzheimers disease, Lewy Body disease, Vascular disease, fronto-temporal dementia and alcohol-related dementia.

It is estimated that currently more than 40,000 New Zealanders have dementia.[i] There are currently up to 40,000 people estimated to have Autism Syndrome and Related Disorders in New Zealand.[ii] By 2026, it is projected that there will be almost 75,000 people with dementia. By 2050, this estimate rises to 150,000 cases.[iii]

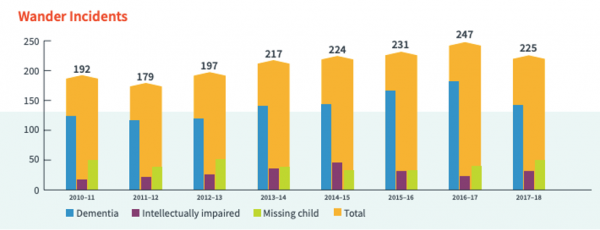

More people with dementia predictably increased the number of so-called ‘wandering’ incidents between 2012 and 2016-17. Yet we can see in the graph below that there was a significant reduction in such incidents over 2017-18. What happened?

Trends in wandering in New Zealand, 2010 to 2017

To respond to the rising trend in wandering rates, the NZSAR Council has been supporting the ‘Safer Walking Framework’, which brings together agencies not typically involved in the search and rescue sector, such as Alzheimer’s NZ, IHC and Autism NZ. This partnership aims to:

-

Reduce the likelihood that people with cognitive impairment will leave a safe environment;

-

Ensure whānau, carers and response agencies are ready should a response be required; and

-

Help locate and return the affected person to a place of safety as quickly as possible.

If this framework is successful, over time we should see the number of wandering incidents reduce, or at least staying stable over time, even if there are more people with dementia. So far, the signs since 2017 are promising, though of course one year of reduced incidents does not constitute a clear trend yet [possible to update to 2020?].

The organisations involved in the Safer Walking Framework have also been exploring the best technologies available to help track people who wander. NZSAR has also funded a research project to investigate alternatives to the existing Wander Search system currently used throughout New Zealand. The work undertaken by WanderSearchNZ and NZ LandSAR so far provides some thoughtful guidance on both the practical options available to track and find people who wander. They are also currently considering the ethical issues associated with using technology such as GPS tracking systems, and even microchipping, to track and find people who wander.

---

[i] NZSAR. (2010, March 22). Workshop for People who Wander. Retrieved October 3, 2017, from http://nzsar.govt.nz/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rq0OTTJWgfk%3D&portalid=4

[ii] NZSAR. (2010, March 22). Workshop for People who Wander. Retrieved October 3, 2017, from http://nzsar.govt.nz/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rq0OTTJWgfk%3D&portalid=4

[iii] NZSAR. (2010, March 22). Workshop for People who Wander. Retrieved October 3, 2017, from http://nzsar.govt.nz/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rq0OTTJWgfk%3D&portalid=4

Diversion - helping people help themselves

Many potential calls for search and rescue assistance are averted either by people getting themselves out of trouble or other services (e.g. Coastguard or Surf Life Saving NZ) dealing with the situation.

For example, the Coastguard deals with many instances when there is not a formal SAR operation underway but help is needed nevertheless.

This can involve going out to give stranded boats fuel so that they can come home under their own power. Such assistance effectively reduces the need for searches and rescues.

As one NZSAR Secretariat staff member put it: “because they do that, it reduces demand on SAR because the boaties are not getting caught on the rocks later.”

Search and Rescue Operations (SAROPs)

For example, it provides a rapid SAR when alerted that someone (or a group of people) is:

- lost and/or hurt (e.g. falling off a cliff) while out walking, tramping, hunting or jogging;

- in a capsized boat in bad weather or one that has mechanical problems or has run out of fuel;

- swept away by a rip or rogue wave while out undertaking outdoor sports like swimming or diving; or

- lost at sea and/or hurt following an air crash.

Formally, a Search and Rescue Operation (SAROP) is an operation undertaken by a Coordinating Authority to locate and retrieve persons missing or in distress.

The intention of the operation is to “save lives, prevent or minimise injuries and remove persons from situations of peril by locating the persons, providing for initial medical care or other needs and then delivering them to a place of safety”.[i]

SAROPs usually have 5 distinct stages:

- Alert (see below)

- Allocation of coordination responsibility

- Diagnosis and intelligence

- Deployment

- Handover

These stages are each set out below...

1. Alert

Alerts occur when:

- a distress beacon is activated;

- somebody calls 111 (e.g. while out tramping); or

- someone requests help via Marine VHF Channel 16 (e.g. while in a boat at sea).

Distress beacons alerts are received directly by the RCCNZ. Beacons are required to be registered at the time of purchase, though around 30% are not). Sometimes calls are also received from automated systems, for example embedded notification systems in many airplanes and on boats. When someone calls 111 seeking search and rescue, the call is received by Police communications centres, then referred to either the Police Search and Rescue Coordinators or the District Command Centres.

When a distress call is made to Marine VHF Channel 16, it is picked up by the New Zealand Distress and Safety Radio Service. This involves both a radio network and operations centre dedicated to issuing weather and navigation warnings and handling distress and safety radio calls within the NAVAREA XIV radio coverage region. The network is a series of radio stations that are tuned to maritime frequencies and linked to Maritime New Zealand’s Maritime Operations Centre (MOC) in Wellington.

Often it is not the person who is lost or hurt that makes the actual call for help. Requests for assistance often come from relatives, friends or even third parties such as hotels (e.g. when they notice that a tourist out on a walk has not checked out of a room at the expected time).

2. Allocation of coordination responsibility

For any SAROP there can only be one Coordinating Authority who is responsible for

the management and coordination of the operation. The New Zealand Police and the Rescue Coordination Centre New Zealand are the recognised Coordinating Authorities in New Zealand.

Alerts are sorted into either category 1 or 2. There are protocols in place that determine how responsibility for alerts is allocated and who becomes the Coordinating Authority in a given situation.

Category 1 SAROPs are coordinated at the local level. They include land operations, subterranean operations, river, lake and inland waterway operations and close-to-shore marine operations. By contrast, Category 2 SAROPs are coordinated at the national level. They include operations associated with missing aircraft or aircraft in distress and offshore marine operations within the New Zealand Search and Rescue Region.[i] During 2015/16, NZ Police coordinated 64.2% of all SAR incidents and RCCNZ the remaining 35.7%. Over time, there has been an increase in the Category 2 SAR coordination efforts.

3. Diagnosis and intelligence gathering

A significant amount of work goes into diagnosing the kind of SAR response required. Each response is treated as unique and depends on:

- the environment – whether the incident has happened on land (bush, urban, cave or alpine), in water (sea, waterway or lake) or air (typically an aircraft lost at sea or in the bush);

- the urgency – for example someone stuck on a mountain or in the sea in freezing temperatures will require more urgent attention than someone who is simply stranded in a hut on a hill surrounded by flooding rivers;

- the distance – whether the event is classified as ‘close’ or ‘far’, including whether it is in a remote area either within New Zealand or other part of the NZSRR; and

- the ease of location – whether the location of the distress signal is well pinpointed. A search is required if the location is not known precisely. By contrast, an extraction or recovery can be more easily undertaken if the location is known. Sometimes there is very poor information about the location provided, such as a recent alert that someone’s partner was lost in “the Dararuas [sic] for a track that starts with K.” In this case, a search rather than extraction would be required at the outset.

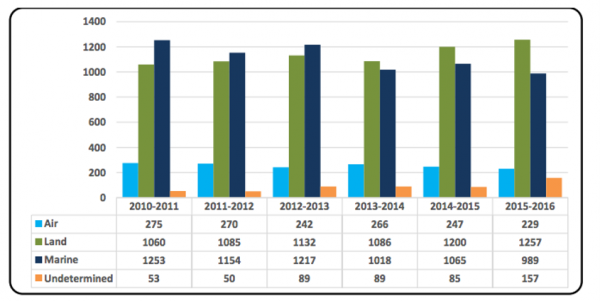

The SAR sector responds to a wide variety of situations throughout the NZSRR and occasionally beyond. SAR incidents can be broken down into air, land, marine and ‘other’ categories. As shown by the graph below, the vast majority of SAR incidents take place either on land or in a marine environment.

While the total number of SAR incidents has remained steady, there has been a decrease in the number of marine incidents and an increase in the number of land incidents over the last 6 years.

SAR incidents by environment

4. Deployment

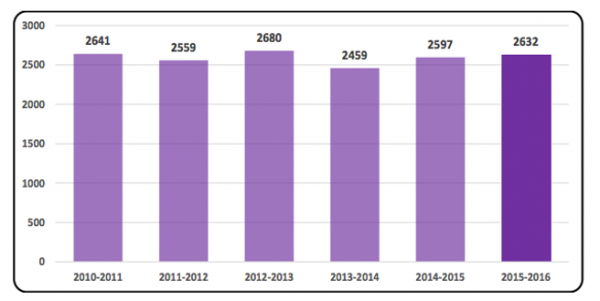

At the same time as rapid collection of intelligence is taking place, an assessment occurs around which assets and people are available and able to be deployed, and how to coordinate that deployment. During the 2016/17 year, there were 2,643 alerts, and which were then classified as SAR incidents, an average of 7.2 incidents per day (data on actual deployments is not collected at present). The total number of SAR incidents over the last 7 years has remained steady, suggesting demand is neither spiking nor plunging, as demonstrated by the figure below.

Total number of SAR Incidents

Total number of SAR incidents, by year

More incidents happen over the summer months between December and February than at other times in the year, presumably because more people are taking advantage of better weather for outdoor recreation at those times. As the NZSAR Secretariat has commented: “if our weather improves, demand spikes...but rapid changes in weather are the real enemy.” Over 2016/17, SAR agencies successfully saved 160 lives, rescued 670 people and assisted 927 others.

5. Handover

SAR operations end when a person has been either recovered (in fatal incidents) or when the person/people are at a “place of safety”. This process is defined in the operational manual and usually involves SAR forces handing over to another entity like an ambulance or hospital.

---

[i] NZSAR. “Coordinating Definitions and Responsibilities”, 1 Jul 2008, http://nzsar.govt.nz/Portals/4/Publications/Policies/NZSAR%20Coordinating%20Definitions%20and%20Responsibilities.pdf