Social trends and volunteering

Page updated: 29 December 2020

There is a common assumption that younger generations are simply less interested in committing to volunteering than older ones.

Is this true, or is there more to the volunteer recruitment challenge than meets the eye?

At first blush, it looks like people are less keen to volunteer

At first blush, the statistics on volunteering make it look like younger generations are simply less interested in volunteering.

A recent report for NZSAR confirmed several key trends in volunteering both overseas and in New Zealand.

These were:

- people are giving less of their time - the total number of hours volunteered fell by 42% between 2004 and 2013;

- people are volunteering more episodically - there are many more people volunteering, but each is doing less; and

- there is a rise in spontaneous temporary volunteering, facilitated by social media (Volunteering New Zealand 2019).

“The mode of volunteering seems to have shifted. People seem to be less willing to contribute/contribute to medium/long term volunteer roles, but happy enough to volunteer hours / half day / day when it suits them.” (Volunteering New Zealand 2019).

Volunteering is no longer a question of ‘many hands make light work’. Instead, a few hands are doing most of it at present. Sometimes referred to as a ‘civic core’, around 14% of volunteers do half of all the hours volunteered in New Zealand, raising issued of both burnout and succession planning.

Is the fix simply to offer more one-off volunteering opportunities?

For some voluntary agencies, responding to these changing social trends and generational values is pretty straightforward; simply offer more opportunities for people to volunteer in the way they want to.

For example, several organisations like Volunteering Solutions, go Abroad, Go Overseas have specially curated “2 Weeks Special Volunteering Programmes”, in which individuals can experience volunteering over a period of just 14 days.

Yet this raises a particularly tricky challenge for the SAR sector. The sector needs its workforce (or at least some parts of it) to be highly trained. This is difficult to achieve without at least some volunteers making a long term commitment. As the manager of the NZSAR Secretariat, Duncan Ferner, observes:

"Trends in New Zealand show that people who volunteer are shifting to episodic and shorter term volunteering. By contrast, SAR volunteers are highly trained, requiring a long term commitment.”

Consequently, simply offering more episodic opportunities to volunteer in future may not be a suitable strategy for the SAR sector to safeguard sufficient numbers in future.

While offering more episodic training opportunities might help, to really grapple with the challenge, the SAR sector arguably needs to better understand the new generations it wants to attract and potentially explore whether a greater proportion of paid workers might be appropriate.

Why the reluctance to commit?

In terms of attracting new volunteers from younger generations, it is fairly clear what they appear to ‘want’ in terms of volunteering opportunities…at least at a surface level.

For example, volunteers from Gen Y and the Millennial generation appear more often to be looking for opportunities to volunteer that involve some very specific attributes such as “small amounts of time, easy to access, immediate, convenient, focused tasks, informal agreement, and ability to explore.” (Roy 2018)

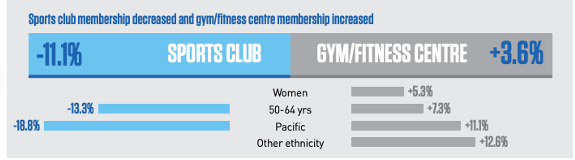

This shift looks, at first blush, like a change in values, particularly among Gen X and Y. It also stretches beyond the SAR sector. We can see it manifested through other similar trends, such as a frequently-reported decline in trust and membership of other formal institutions such as clubs and churches. For example, the 2017 environmental scan highlighted that now only 8% of New Zealanders are part of a club. Over a 16 year period to 2014, sports club membership decreased by 11.1% while gym membership increased by 3.6%.

Declining Sports Club Membership (Sport NZ, 2019)

This reluctance to commit to institutions is not limited to New Zealand either. A 2014 performance audit of New South Wales’ State Emergency Services (SES) observed that “twenty six percent of SES volunteers leave each year, many soon after joining” and concluded that the “SES cannot be assured that it has sufficient volunteers to respond to future demands.” (Calcutt 2019) Research from the Stanford Graduate School of Business similarly found that “more than one-third of those who volunteer one year do not donate their time the next year at any non-profit.” (Eisner, et al. 2009)

One possible explanation about what is driving this reduced tendency to commit to voluntary organisations is that people increasingly want to avoid getting locked in, lest they find themselves unable to meet their own array of other life obligations. One commentator elaborated on this theory, saying:

"In today's date, everyone is busy managing their work life, socialising, going to the gym, pursuing their hobbies, getting adequate "me time" etc., which are restraining us from long-term commitments. Thus, a considerable growth in the demand for short-term volunteering has also left this sector struggling to utilise this demand by providing enough opportunities and supporting this shift in the nature of how some people would like to volunteer." (Roy 2018)

Does the reluctance to commit mean the end of volunteering?

So, does this mean we seeing an inexorable shift to a future where volunteering inexorably declines? Not necessarily.

Glimmers of hope

It would be wrong to conclude that volunteering will inevitably fade away. For example, in 2017, New Zealand was actually ranked as number 6 globally in terms of the number of hours and percentage of people who volunteered (Volunteering NZ 2017). Even more encouragingly, there is data to suggest that younger generations are more likely to want to volunteer than the generations above them.

For example, between 2016 and 2018, the volunteering rate in the USA actually grew from 24.9% to 30.3% (National and Community Service 2020). The same research showed that people from Generation X were actually the most likely to volunteer, with 36.4% of Gen X Americans volunteering (National and Community Service 2020).

Similarly, data from Ipsos MORI’s Young People Omnibus among school children in Britain, shows there has been a cohort shift towards higher social activism.

- Nearly half of 14-16 year olds (46%) say they have given their time to help out people in the community in the past two years, compared with just 30% in 2005.

- Three in ten (29%) are regularly active in their neighbourhood, community or an ethnic organisation compared with just one in ten (10%) in 2005 (Ipsos 2018).

Also, there is also some evidence that the reduced trust in institutions and other people demonstrated by Gen Y and the Millennials, is not necessarily going to endure through to Gen Z. For example, research has shown that Generation Z are nearly twice as trusting than Millennials were at the same age (61% in 2017 compared to 36% in 2002) (Ipsos 2018).

No, but the SAR sector does need to cater to younger cohorts better

One challenge for all institutions seeking to attract young people is understanding how best to inspire and retain their trust and commitment. Another is to evolve their workforce models to fit flexibly with the reality of volunteers’ lives (e.g. finding ways to help potential volunteers to balance study, work and other commitments).

Much of the decision about whether to volunteer, and how much, is driven simply by the perception people hold about how much time they have available after doing ‘essential’ things like sleeping, working and meeting family obligations.

|

“Younger volunteers are motivated by more specifically focussed issues affecting them and the future of their families” (Volunteering NZ 2017) |

In 2017, women volunteered 1.8 million more hours than men. Why? Simply put, they had more available time for volunteering (or prioritised it more highly) because they spent less time in the paid labour force (Statistics NZ 2017).

Does this mean that if people consider voluntary work as valuable as paid employment in future, it might be possible to unlock significantly greater commitment from them? Or does it mean that, given women are increasingly participating in full-time paid work, we should expect and accept that volunteering will inevitably decline?

The important point here is that the future is not a foregone conclusion. The answer to these questions will depend on what factors into peoples’ decisions about how to spend their time.

So, a key question facing the SAR sector is whether to accept and work with the ‘too busy’ narrative going forward, or to try to shape potential volunteers’ perceptions.

As highlighted in the section on social trends, the sector is already hard at work shaping perceptions when it comes to encouraging people to prepare before venturing into the outdoors. Why not also try to shape perceptions around time use in the same way to attract and retain more volunteers, and even induce them to make longer-term commitments?

Understanding and influencing future volunteers

If the SAR sector decides it wants to influence the potential volunteers’ perceptions and values around time use, the next big question is clearly how to do so successfully.

One way to do this is to start by trying to better understand the values of younger generations.

Values represent the overriding, governing motivation for decision-making, and they matter a lot. If you want to inspire any group of people to commit to volunteering, you need to understand their values and ensure that your messaging resounds.

A key challenge for the SAR sector may be working out how to convert the willingness of different generations to volunteer in the short term, into a longer term commitment to training and ongoing service.

To do this, the sector might usefully consider how to present volunteering opportunities in terms of the values and expectations that are most likely to resound with different demographics.

A values-led approach to attracting new volunteers

Taking a values-driven approach may mean adopting very different strategies depending on the target demographic.

For example, instead of looking to acquire cars and houses, there is some evidence that the Millennial generation is assigning greater importance to personal experiences – and showing off pictures of them (Boston Consulting Group 2016). For example, research has also shown that, until COVID-19, today’s 20-somethings were spending more on travel than they were traditional investments - like down payments on homes. For example, in the year to October 2017, New Zealand residents departed on 2.83 million trips overseas, up 271,800 (11 percent) from the previous year (Statistics NZ 2017).

Millennial travellers weren’t heading to Europe, Southeast Asia and South America to party. Instead, their trips were all about authenticity and cultural immersion (Mya 2019). Research into the motivations for Millennials travelling suggest they wanted to:

- Experience authentic different cultures;

- Find themselves, including the courage to embark on different careers or life trajectories;

- Set themselves apart, being seen as trail blazers;

- Be more physically active than previous generations; and

- Repeat what they see on social media (Mya 2019).

Furthermore, there is a sense that Millennials can be attracted by the offer of ‘making a difference in the world’. Perhaps the opportunities Greta Thunberg has provided to her millions of global followers demonstrates best practice here. Just 16, she has inspired hundreds of youth climate protests across more than 100 cities worldwide (CNN 2019). Her brand is one of straight-talking authenticity and actively encouraging young people to belong to a wider movement for change; both things that appeal deeply to younger generations.

These insights arguably give the SAR sector a sense of the ‘hooks’ required to interest younger generations, like Millennials, into volunteering.

There is no reason that volunteering opportunities in the SAR sector could not be presented to younger demographics in a way that highlights the value of authentic life experience, particularly given that opportunities to travel are now severely curtailed in the short to medium term for everyone.

The kinds of experiences SAR agencies might offer could, for example, relate to both ‘intangible life experiences’ (such as saving a life) and the kind of experiences that will benefit them personally (e.g. experience which can be put on a CV an improve future work prospects).

Of course, pursuing a volunteering recruitment strategy based on population segmentation needs to be done with care. It is easy to over-simplify the approach, which could come off as insincere and easily backfire. For example, when it comes to Millennials, there is also a so-called ‘perfection paradox’ to navigate. In short, while people from this generation tend to value authenticity, it is not at all costs. As one commentator put it:

“Though they love to show their authentic selves, they also know that pimples do not generate likes, and neither do old clothes, fuzzy hair or an ordinary cheese sandwich. In other words: reality outplays perfection, but appeal outplays reality.” (Ipsos 2018)

If the SAR sector wants to attract and retain younger volunteers so as to create a sustainable future workforce, they will need to understand them and target them sensitively. For example, one approach could be to ensure that all opportunities to volunteer area marketed to this demographic with three key things: a clear statement of why their contribution matters (meaningful purpose), the opportunity to gain authentic life experience, and something that they can post to their Facebook, Snapchat or Twitter feed.

Obviously the kinds of approach being made to older generations to induce them to keep volunteering would need to differ again based on further insights about the values and priorities driving them.

Recognising volunteers remains important too

Of course, peoples’ willingness to volunteer is not just a question of their attitudes and willingness, but also their availability. As highlighted in the section on social trends, most New Zealanders are feeling busier and more pressed for time. This suggest that finding ways to avoid volunteers having to make difficult time trade-offs may also be a valuable way to safeguard the future SAR workforce.

One option might be to explore partnerships with supportive government agencies or businesses who might donate a proportion of their employees paid work time to volunteering for the SAR sector.

Among companies that already offer their employees time off to volunteer overseas are Google, SpaceX, Johnson & Johnson and Southwest Airlines (TSheets 2017).

The Bank of America boasts that its employees volunteer 2 million hours annually (Bank of America 2020). As well as providing paid time off for volunteers, it also provides grants for organisations where employees volunteer regularly and celebrates employees’ impact through a quarterly and annual honour roll and annual Global Volunteer Awards.

It may also be possible to convince government to contribute funding to such a scheme. For example, in August 2016, the City of Aurora, Colorado announced a new Employee Volunteer Programme, giving full-time employees eight hours and part-time employees four hours of Paid Volunteering Time Off (PVTO) every year (Keyser 2018). A month later, the Town of Mooresville, North Carolina also launched a similar volunteer programme, with the director of Human Resources there stating:

“We had some employees express concern that they could not afford to donate to every worthy cause that came their way. They were willing to donate time, but money was the issue. This policy was developed as a way for employees to give back to their community without a financial burden.” (Keyser 2018)

It is important to note that most PVTO schemes do not fully reimburse volunteers for all the time they spend volunteering. However, it may be that a partial reimbursement is useful to signal both that volunteering for SAR agencies is a worthwhile thing to do and even to secure a long-term commitment from volunteers.

This said, it will be important to ensure that introducing extrinsic incentives, like partial reimbursement, does not inadvertently crowd out intrinsic ones when it comes to volunteering. For example, in the past, researchers have found that paying for people to donate blood actually reduces the number of people who donate because it the displaces natural altruistic motivation with a financial motivation – which turns out to attract fewer people to donate (Titmuss 1997).

Ultimately, the most effective strategy for attracting and retaining volunteers in the SAR sector is an empirical question. So, perhaps an experimental approach with a focus on trying different things and systematically learning what works is most advisable. It may also be that different things work to attract volunteers into different parts of the SAR sector.

Lowering barriers to entry (make it easier for people to sign up)

There is a significant body of evidence to suggest that once people make an explicit commitment to a cause publicly, and start actually doing it, they are much more likely to continue, regardless of how committed they were at the outset.

Part of the reason that securing a small initial commitment from potential volunteers can lead to a much bigger one is that humans are near-obsessed with appearing consistent in our own words and actions.

For example, in one experiment, researchers asked participants whether they could erect a large and unsightly wooden sign on the front lawn of different homeowners to support a ‘drive safely’ campaign. The researchers found that four times as many homeowners in one particular neighbourhood agreed to put up the signs.

What was different about the ‘high compliance’ neighbourhood?

Ten days beforehand, the homeowners in that particular neighbourhood had already been asked to place a small and discrete postcard in their front windows that signalled their support for the same campaign. Because it was so unobtrusive, most people agreed to this request readily. But, because the researchers had their ‘foot in the door’ with these homeowners, it was then much easier to get them to agree to a much bigger sign later. As influence expert, Robert Cialdini puts it “that small card was the initial commitment that led to a 400% increase in a much bigger, but still consistent change” (Cialdini 2006).