Climate change

Page updated: 7 January 2021

The reality of impending climate change is no longer the subect of serious debate by scientists around the world. But what will be the impacts on New Zealand specifically and the Search and Rescue (SAR) sector?

Global warming is well underway

It is time to move beyond the question of whether climate change is real (which it is), to the challenge of how to adapt best to the impending reality.

When scientists talk about global warming, the numbers they use seem small, but the future impacts are likely to be enormous in reality.

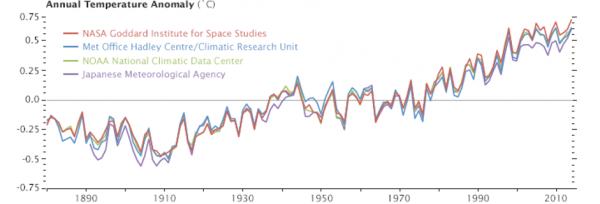

The average global temperature on earth has increased by about 0.8 degrees Celsius since 1990. Two-thirds of the warming has occurred since 1975, at a rate of roughly 0.15-0.20 degrees per decade.

While this might seem like a small amount, it is actually significant because it represents an average over the entire surface of the planet. It takes a huge amount of heat to warm all the oceans, atmosphere and land by that much. In the past, a one- to two-degree drop was all it took to plunge the earth into the Little Ice Age.

Some people stuggle with the notion that the average temperature is increasing. This has led some scientists to adopt the term 'global weirding' instead to convey what the symptoms of global warming are likely to look like - i.e. more weird extremes in weather patterns.

These kinds of extremes, which accompany the general average increase in temperature, are evident in the graph below. In short, the more extreme annual temperature anomalies are becoming far more common is a symptom of climate change.

In light of this clear evidence of climate change, the question is now how severe the impacts of climate change are going to be, and how to plan to mitigate them going forward.

The SAR sector is likely to face significant impacts in particular, which will drive increased demand both in New Zealand and across the Pacific. All nations in the Pacific are likely to be subjected to rising sea levels, causing more flooding, and much more severe weather such as cyclones and storms.

The impacts are acccelerating

The impacts of global warming on the weather so far are already well documented, fuelling “sea level rises, heatwaves, storms and the decline of vulnerable ecosystems such as coral reefs.” (Milman 2018) What is even more concerning is that the impacts of climate change appear to be accelerating exponentially.

It used to be that we talking about climate change as a future problem.

Now there is clear evidence it is occuring at an accelerating rate right now. For example, 2020 was again a record year in terms of global temperatures, as marine heat waves swelled over 80 percent of the world’s oceans, and triple-digit heat invaded Siberia, one of the planet’s coldest places.[1]

Most recently, scientists linked devastating hurricanes in the US, record droughts in Cape Town, forest fires in the Arctic (Watts, Jonathan; Taylor, Matthew 2018) and so-called ‘mega-blazes’ in Australia all to the current effects of climate change.

The Australian bushfires have also claimed many lives, burnt millions of acres of farmland and bush and destroyed 400 homes (Kelly 2020).

Satellites monitoring the state of Antarctica indicate some 200 billion tonnes of ice a year are now being lost to the ocean as a result of melting. This is pushing up global sea levels by 0.6mm annually - a three-fold increase since 2012 when the last such assessment was undertaken.[2]

Scientists have also linked recent mass coral bleaching events and reductions in biodiversity to climate change. Petteri Taalas, the secretary general of the World Meterological Organisation, said in a news release that there is at least a 1-in-5 chance of the global average temperature temporarily exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.4 Fahrenheit) by 2024. This would be significant because that is a guardrail established under the Paris climate agreement, and residents of many low-lying small island states regard it as the threshold beyond which they face an existential risk from sea-level rise.[1]

Furthermore, the author of a key UN climate report says that the world is ‘nowhere near on track’ to avoiding global warming beyond the 1.5C pre-industrial period target.

U.N. Secretary General António Guterres has commented that:

Every 10th of a degree of warming matters, and today we are at 1.2 degrees [Celsius] of warming and already witnessing unprecedented climate extremes and volatility, in every region and on every continent,” Guterres said, comparing global average surface temperatures today with the average from 1850 to 1900."[1]

The lack of progress on mitigating climate change is perhaps not surprising as the former US President Donald Trump announced that the USA was pulling out of the Paris climate accord, and the Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison said in 2020 that there was no money for “global climate conferences and all that nonsense.” (Watts, Jonathan; Taylor, Matthew 2018).

In contrast, there is now a scientific consensus that climate change, no matter what happens now, is leading to more extreme weather events, coastal and river flooding, and large-scale singular events such as ice sheet collapses.

---

[1] Freedman, Andrew (3 Dec 2020). “Pace of climate change shown in new report has humanity on ‘suicidal’ path, U.N. leader warns”, The Washington Post, Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

[2] Amos, J. and Gill, V., (13 June 2018). “Antarctica loses three trillion tonnes of ice in 25 years.” https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-44470208, Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

New Zealand is already feeling the heat

The impacts of climate change are already being felt globally, and the heat is already starting to be felt in New Zealand and across the wider Pacific Search and Rescue Region.

One forecast of what to expect went as follows:

Long, hot summers will be more common. It will likely rain more on the West Coast and less in most of the rest of the country, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, drought conditions will increase.

Meanwhile, the sea will rise by about 20 to 30cm, while extreme winds are likely to increase in eastern regions, but humidity is set to reduce everywhere except the West Coast. (Radio NZ 2019)

There are already many indications that New Zealand is already beginning to experience the effects of global warming. For example, many parts of the country experienced their warmest year on record in 2019. These included:

- Chatham Islands – 1.7 degrees above average (records began 1878);

- Blenheim – 1.2 degrees above average (records began 1932);

- Dunedin – 1.1 degrees above average (records began 1867);

- Rotorua – 1.1 degrees above average (records began 1886); and

- Invercargill – 1.0 degree above average (records began 1911) (Zaki 2020).

In New Zealand, the Ministry for the Environment says extreme coastal water levels, currently expected to be reached or exceeded once every 100 years, will, by 2050-2070, occur on average at least once a year (Blundell 2018).

More heat = more disasters = tougher SAR context

The increased probability of major, as well as more frequent, disasters is likely to drive increased demand for New Zealand’s search and rescue services both on the mainland and across the wider NZ search and rescue region.

Rising seas are a particular concern across the Pacific region, particularly due to the many low-lying coral islands located at sea level.

Ocean warming, frequent tropical cyclones, flash floods and droughts are all likely to have a dramatic impact on the New Zealand mainland, and in particular are increasingly likely to be the context of SAR operations.

NZ Herald, 29 May 2019

In the future, the Pacific region can also expect widespread increases in extreme rainfall events, large increases in the incidence of hot days and warm nights.

While uncertainties remain for tropical cyclone projections, they are projected to occur less frequently in the Pacific Ocean over the 21st century. However, projections do suggest an increase in the proportion of storms in the more intense categories.[iii]

The changes in weather patterns undermine local knowledge – which is normally one of the most powerful assets in predicting and managing impacts for organisations and sectors like SAR.

The uptick in disasters is also likely to lead to a much higher probability and frequency of need for Mass Rescue Operations (MROs) in future.

---

[i]“The Impact of Climate Change on the Pacific.” Social Sciences and Humanities - Research & Innovation - European Commission, ec.europa.eu/research/social-sciences/index.cfm?pg=newspage&item=151130.

[ii]Chapman, Paul. “Entire Nation of Kiribati to Be Relocated over Rising Sea Level Threat.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 7 Mar. 2012, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/kiribati/9127576/Entire-nation-of-Kiribati-to-be-relocated-over-rising-sea-level-threat.html.

[iii]Scott B. Power Senior Principal Research Scientist, Australian Bureau of Meteorology. “Climate Change and the Future of Our Pacific Neighbours.” The Conversation, 29 Aug. 2017, theconversation.com/climate-change-and-the-future-of-our-pacific-neighbours-4512.

The SAR sector needs to start adapting now

The effects of climate change are likely to become exponentially greater over time. In this context, if the sector waits too long, it will be too busy dealing with daily crises to plan ahead. This makes now the right time to plan ahead and adapt SAR services to the new, tougher environmental context.

To be able to plan and prepare for the effects of climate change, SAR agencies need to plan and prepare for new disaster patterns, intensities and probabilities.

The sector will need to find novel ways to ensure help is available when needed across the entirety of the NZ Search and Rescue region.

Given the massive size of this region, this is no small task.

In particular, the climate change challenge is likely to require more modelling, consideration and adaptative organisational planning by all search and rescue agencies than ever before.

As one report on climate change put it starkly:

“Disasters are not exceptional any more: They are the norm. We, and the governments that serve us, better start treating them that way.” (Older 2019)